“As a landscape architect and a planner, architecture has a more timeless notion to me. What we should make is creating good cities and living environments that people are happy with now and one hundred years from now, places that are easy to transform and can gradually change themselves.“

Andreea Robu-Movilă: How did it all start?

M.K.: We started working in the Netherlands and had really good projects for a young office. That was a big opportunity to learn a lot, but also to give a lot without having the pressure of working in a big city. Gradually, this project became popular and people from all the cities were coming to us for different works. One of our big steps was to change the cityscape of Rotterdam, our harbor city. During that project we developed different ways of changing infrastructure and creating better environments on a city scale, whilst working on other assignments. That was a big step for us and it helped us tackle the international scene.

A.R.M.: Have you worked for big offices in the first years of practice?

M.K.: We were four guys who had the idea to start an office and we just started it without a business plan, without clients, without anything…

A.R.M.: So without any experience… That was very brave!

M.K.: Yes, it was! Sometimes people ask me “How did you do it?”

A.R.M.: Really… How did you do it?

M.K.: I tell them “Don’t do it like we did. I know it worked but it’s not a natural way of doing it.” Usually you have clients, a network and a name, so you can start your architectural office. We just did it, won some competitions and it gradually succeeded.

A.R.M.: How did you manage to build the project after winning a competition? Did you seek advice from other architects?

M.K.: We always work in teams. During the first years our office worked a lot for the cities: many people from city departments were also our partners, so we had a network and the technical discipline to get it done.

A.R.M.: How do you see the state of architecture in your country?

M.K.: When we started public ground was not that important. It gradually gained importance and architecture was also changing from the buildings in the ’90s, which proved good architectural approach, to a more audacious and challenging architecture. Whilst our profession grew, we were also growing within.

A.R.M.: What was the biggest challenge of your career?

M.K.: We think it is really important to work on items that are really interesting for our society. At this moment we should work on climate-adaptive solutions for cities, we should work on well structured meeting places for cities so that citizens can interact and we should be aware that we are now moving towards a circular economy. That means energy production, water solutions and all these kinds of things should be integrated within our design process.

A.R.M.: You seem to be interested in large scale projects like modeling the city landscape. What about the small projects?

M.K.: We mostly work on large scale projects because this gives us the opportunity to really change something. The more complex a project, the more we like it. Sometimes a small project can also be challenging because it connects with all our other projects or it could be a demonstration project for new ideas and theories. We accelerate these to larger scale and get them to the city scale.

A.R.M.: With such great projects I believe you should have a good management department in your office. How do you organize your office in order to approach these large scale projects?

M.K.: We have organized it in an architectonic way. We think that design is a collaborative work, so most importantly is to have a team, not a management structure, but a team. Several people are working on one project and they gradually move from the conceptual phase to later design stages.

A.R.M.: This team is involved in the whole process or do they pass the design to other teams?

M.K.: For me it is important that the same team is working on a project, although the tasks pass from one to the other sometimes. A technical person becomes more important when the technical part is executed. If it’s done really well, the technical person is involved in the early sketches of the concept or at least should know something about it and have something to say.

A.R.M.: What individual qualities do you appreciate the most in an architect?

M.K.: The most important quality is to be a good team player. A good professional knows his design skills and understands how to work with other disciplines, while being aware of concept implementation and its connection with other fields. Above all, an architect should be a teammate. If your ideas do not connect to a client or a person you’re working with, these ideas will get stuck. If you cannot connect with other people, everything stops.

A.R.M.: How do you perceive architecture among the other fields of interest?

M.K.: Our profession is increasing in importance. If you think about the real power within the society, we can agree there is a decrease. Politicians are taking strong leads to push architects away but if you look at the ideas an architect can bring to a city, you realize that we can have a great impact. Politicians, cost calculators and engineers take over but what they cannot take over are great ideas, the ideas that help create buildings and better living environments.

A.R.M.: I am very interested in the way the architects have managed and succeeded to get in touch with the authorities and make their ideas visible. On the other side, architects from Eastern Europe always complain about the poor collaboration with the administration. What can we do to overcome this major setback?

M.K.: We come from a background in which involving all the stakeholders proves to have a great importance, so we try to talk to all the stakeholders from an early stage. By defining a good program for them, this becomes interesting for the politicians as well – whatever political background they might have – because they see that the people voting them are interested in the way the master plan evolves. If we have stakeholder involvement at a later stage, people might not be happy with what is being built, so many unnecessary problems can arise. I think it starts with showcasing the project from the early stages and embrace social involvement.

A.R.M.: Politicians probably understand that they can build up their power through architects and architecture.

M.K.: Yes! In some countries like South Africa we call this “co-creation” because we create living environments together with locals, stakeholders and politicians. This is inducing more enthusiasm over the projects and people start supporting them.

A.R.M.: Isn’t it difficult to control the plethora of ideas from an early stage? I think that is a critical point in the project management.

M.K.: [laughs] We really need to focus and set the rules of the game from the beginning because you can’t fool the audience. If there is a certain budget, you should be clear about it and tell people. If you don’t do it, they start making up dreams that cannot become reality and get disappointed. It is all about organization, honesty and freedom.

A.R.M.: Can you tell us something about your experiences outside the Netherlands?

M.K.: When you work in your own country you are part of the society and its actions. When you work abroad, people see you as a foreign expert, so you need to work with local offices in order to make good connections. You try to find a balance between being there and not being there.

A.R.M.: What is your main source of happiness in architecture?

M.K.: The main source of happiness is if the end-users utilize the space. If you have created an urban space and people are starting to use it and make it their own, then you are successful because it is not just a nice place for the shops, it is a place for the people.

A.R.M.: That’s probably the reason why you like large scale projects so much as they have a significant impact on a community.

M.K.: I think we like to work for a lot of people and people in general, not just individual users.

A.R.M.: Thank you for your time!

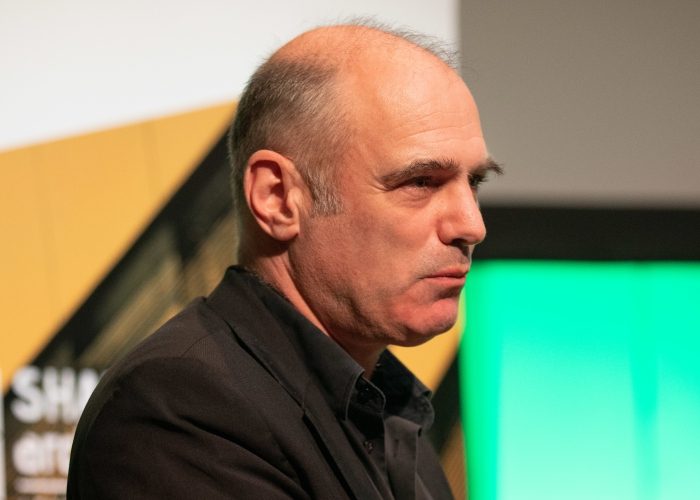

Martin KNUIJT – Director and Founding Partner OKRA LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTS – NETHERLANDS

Martin Knujit is a founding partner of OKRA, , a prominent landscape architecture and urban planning office in The Netherlands. His strength is defining strategic visions and scenarios and creating strong spatial designs. He is mostly active in the design of complex urban and landscape development projects, working to the knot. He is fascinated and driven to integrate socially relevant themes, such as design for all and climate-resilient design. Within his work, themes like connected city, vibrant city, healthy city and attractive city are all interrelated with social, economic and ecological sustainability.

He is mostly active as designer in urban and landscape development projects on a wide range of design assignments. These vary from abstract plans and long-term visions to detailed designs for spatial organisation. Recent projects are amongst others ‘Re-Think Athens’, ‘Vision Public Space Rotterdam city centre’, and ‘Meridian Water, London’. Several lectures, workshops and lectures testify of his involvement on the field of landscape architecture and urban planning. Martin Knuijt was keynote speaker at the IFLA congress in Calgary, the CCCB Biennale in Barcelona, and the EFLA congress in Prague, at the 75 anniversary of TU Berlin and at Tongji University in Shanghai. He is author of a couple of publications on landscape and urban planning, published in several European magazines.

Find out more: https://www.okra.nl/