“At that particular time, when I was working with Zaha, deconstructivism sort of destroyed everything, but it hasn’t been set aside yet, although we feel there are certain challenges we’re all facing globally: sustainability and the complexity of integrating everything into architecture are other aspects related to that. The present is a bit confusing because I cannot recognise the values I am searching for in any project – I see a lot of ‘in your face’ advertisements of shapes and forms and everything is possible; everybody has a good sales story about the righteousness in what they are doing but is it really that good? What makes something convincing and valuable for a longer period of time?”

Mark Hemel: I graduated from university in Holland and did my post doctorate in London at the Architectural Association. It’s quite a different kind of school, attracting a lot of enthusiastic and determined people from all around the world. I wasn’t really productive in my first year because I was raised in a certain way and I had to undo that in order to find myself and what I wanted to do. I did not pass my exams, as Zaha Hadid was in the jury [laughs]. I realised I was completely misunderstanding what I was supposed to be doing. I was focusing on one little panel while all my classmates were doing ten panels and had like a little office of people working like professionals.

Andreea Robu-Movila: Do you owe something to Zaha Hadid?

M.H.: Yes, she also asked me to work in her small office. There were only students or graduates working for free because she didn’t have that many projects at the time. We worked on competitions one after the other and that made me understand how hard you have to work and how precise you have to be.

A.R.M.: How much of an influence did she have on you? Is your style somehow linked to her approaches?

M.H.: No. I think we share certain spatial perspectives.

A.R.M.: And the common background in mathematics. Have you met her since starting on your own?

M.H.: Yes, of course! When we were working on Canton Tower in Guangzhou, I called her for some advice and she was very friendly, kind and willing to help us because we had no experience at all with large projects. She was like a real mentor, but that does not mean that I am copying anything that she has been doing – people’s qualities are the things you start to appreciate.

A.R.M.: When you opened your office, were you working by yourself?

M.H.: I started it in 1998, together with my wife, who worked with Philippe Starck and later with Zaha. We are a complementary team!

A.R.M.: How big is your office now?

M.H.: It depends a lot on the projects. We can have more than twenty people on large projects but we’re still not that big of an office.

A.R.M.: What is the project you take the most pride in?

M.H.: I still think I cannot get over the Guangzhou Tower because of the way it was received by the community.

A.R.M.: It had a great impact on people?

M.H.: Yes! We worked on many interesting projects early on in our career but I never thought there would be many more, not at that rate anyway.

A.R.M.: Do you have a permanent collaborator for structural engineering?

M.H.: We started working with ARUP because they are a very big and professional engineering firm, and we prefer to operate with those kinds of engineers. They are kind of progressive and always interested in the newest technologies and that’s what we are looking for.

A.R.M.: How do you see the future of architecture?

M.H.: It’s difficult to predict the future, but I think what architects do is try to create a sort of resonance with the contemporary. They search for the predominant theme at any moment in time and try to create the best expression of that with the hope that it will last, in a way.

A.R.M.: What has changed since you worked with Zaha? What can you do today that was not possible then?

M.H.: The fact that many more things can be integrated, which also makes nowadays a more confusing time. At that particular time, when I was working with Zaha, deconstructivism – this was in opposition to postmodernism – sort of destroyed everything, but it hasn’t been set aside yet, although we feel there are certain challenges we’re all facing globally: sustainability and the complexity of integrating everything into architecture are other aspects related to that. However, I have not seen very promising things yet – I suppose it is floating in the air and everybody is thinking in that direction but who can create an architectural language that is based on that? The present is a bit confusing because I cannot recognise the values I am searching for in any project – I see a lot of ‘in your face’ advertisements of shapes and forms and everything is possible; everybody has a good sales story about the righteousness in what they are doing but is it really that good? What makes something convincing and valuable for a longer period of time?

A.R.M.: What is good architecture for you?

M.H.: I think like a cook, basically. I’m looking for the best possible ingredients to make a dinner and since I’m interested in architecture, I want to make a long lasting dinner… I’m not interested in the latest trends; instead, I am looking for the core aspects of architecture. To me, there is a certain truthfulness or sustainability, by definition, because good architecture is real and is made to stay there and grow as time passes. Architecture has to show some kind of beauty – not necessarily an aesthetic beauty – that touches you in a significant manner.

A.R.M.: What do you think the role of the architect is today in our society?

M.H.: I think an architect is like a moderator or an interpreter for society. With the development of the virtual world, there is also a rising eagerness for certain physical aspects. I live in Amsterdam, which is basically a 17th-century space, so we will always live in spaces and those spaces offer some strange disconnections because you happen to live in a place that was devised several centuries ago.

A.R.M.: Looking to the future, what are the values an architect should invest the most in?

M.H.: Being relevant! By showing too much advertising and too many conceptual levels of architecture, you can make yourself irrelevant, as people can see through these ‘catchy phrases’. As an architect, you cannot constantly be standing next to your building reminding people why it is so good.

A.R.M.: Indeed. Each work should speak for itself, but I wonder how young architects can learn to be relevant.

M.H.: They should find the time to focus on themselves.

A.R.M.: What about education?

M.H.: I think education is problematic by definition.

A.R.M.: I wonder if we will always perceive it as problematic as we need to understand that it is basically an institution that works slower than the changes over time and it will always be one step behind these continuous changes.

M.H.: I’ve taught for a very long time – around 25 years. Of course, it is very interesting to work with students because you get in contact with younger people who have different visions but you have to be careful as a teacher not to have a negative influence on them by putting forward too many of your own ideas. The education system should be organised in such a way that it enables the existence of so many different ideas and makes it possible to select some of them.

A.R.M.: Do you take other fields into consideration when it comes to organising your practice? And is it structured?

M.H.: We work in small teams and this is quite normal in Holland. It’s a non-hierarchical structure, so everybody can have a say, but at the same time every project has deadlines or time pressures and you have to make some decisions. It’s not organised in a fixed way – not like a machine anyway…

A.R.M.: But it has the advantage of being a flexible system that offers a lot of space for creativity.

M.H.: It is also open to mistakes and new ideas all the time.

A.R.M.: What criteria do you use to select people working at your office?

M.H.: I find it very, very difficult because we get lots of applications. It is mainly a certain mentality that you’re looking for – somebody who loves architecture and is willing to dedicate themselves to it. As an architect, you need to be serious and accurate and possess that drive to make things better.

A.R.M.: Considering the name of your office – Information Based Architecture – are you related to the field of information technology in any way?

M.H.: No, it just has to do with the fact that at the basis of architecture there are some ingredients – the aspects that you base everything on. The idea for the office started in the ’80s when computers were being developed and anything was possible. I wanted to research things at the basis of architecture and use that information like a kind of DNA – we try to develop a DNA for each project.

A.R.M.: How do you feel about the application of artificial intelligence to architecture?

M.H.: The way you’re using Google today is by asking questions and that is why it knows almost everything about you. It also has a much better memory than us and can make better and more informed decisions then we can. But we have a version of it – intuition – that is a sort of vague understanding of things.

A.R.M.: There is a lot of information that we get subconsciously. There are a lot of things you can find out about a client when you meet him even though you don’t realise it at that very moment.

M.H.: Depending on how your mind is built, you have more cross connections or fewer. Therefore, you are all over the place or you are very determined and rational. I suppose that is the same thing they are trying to build for big data – interpreters or search engines like Google offer. In the end, everything is just chemicals, so there is the possibility that we will all become irrelevant, not just architecture [laughs]. It’s not such a positive prediction but it’s actually closer than you might think. However, that is also something you can decide as a person – you can choose to be optimistic and you can do everything in your power to understand and steer this direction in order to move forward.

A.R.M.: Do machines have limits?

M.H.: I think the big difference is that machines will be radical if they start to develop on their own. For example, there is a common story in the field of AI about the paper clip apocalypse. The thought experiment goes like this: suppose that someone programs and switches on an AI that has the goal of producing paper clips. The AI is given the ability to learn, so that it can invent new ways of better achieving its goal. As the AI is super-intelligent, if there is a way of turning something into a paper clip, it will find it. It will want to secure resources for that purpose. We might want to stop this AI. But it is single-minded and would realise that this would subvert its goal. Consequently, the AI would become focused on its own survival and start fighting humans for resources, but now it would want to fight humans because they are a threat. A human always has feelings and he can always base his decisions on his rational side.

A.R.M.: We find ourselves extremely interested in developing artificial intelligence and I think that happens because of our desire to create… in creating intelligence…

M.H.: Just like any tool, you can use big data and artificial intelligence to your advantage but you can also shut it off if it has the potential to become dangerous. When steel was introduced to architecture, there were probably visionary ideas about its use but everybody made a decision about how to use it. As far as all novelties are concerned, we should be in control, make our own decisions and stay optimistic.

A.R.M.: Thank you for your time!

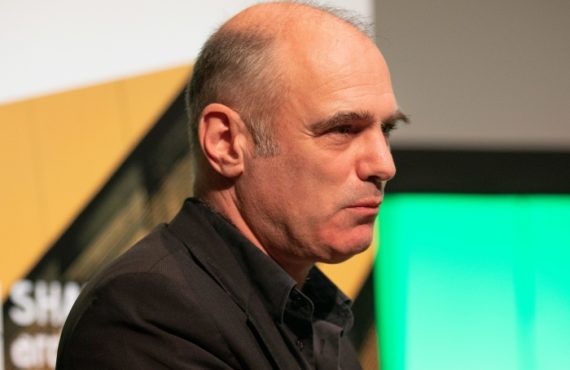

Mark Hemel – Architect, Designer & Co-founder of IBA

Mark Hemel (born 1966 in Emmen, Netherlands) is a Dutch architect and designer, and co-founder (with Barbara Kuit) of the Amsterdam-based architectural practice Information Based Architecture (IBA). He is best known as the (co) architect of the Canton Tower in Guangzhou.

Hemel co-founded the firm Information Based Architecture together with his partner Barbara Kuit in 1998 while they were still based in London. The office is called “information based” in order to clearly break with the common state of architecture at that time that was producing uninformed “blobs”. In 2003 they moved their office to Amsterdam, while they focus their work currently on Europe, China and Africa. They have won several high-profile competitions, the most important being the design for the 600 metres (2,000 ft) tall Canton Tower which has recently been opened to the public.

Hemel was educated by American theorist Jeffrey Kipniss and UK architect Zaha Hadid as well as Dutch architects Herman Herzberger and Carel Weeber. He was particularly influenced by books of Richard Dawkins (The Selfish Gene 1976) Kevin Kelly (Out of Control1995), Ilya Prigogine (Order Out of Chaos 1984) and Douglas Hofstadter (Gödel, Escher, Bach). After his post graduate studies at the Architectural Association in London Mark began teaching at the AA.

Mark’s focus is on “global architecture”. His main interest is to play a role in the expression and development of our contemporary culture. In his view Architecture can play an important and positive role in shedding light on potential routes “our” global culture could take.

Mark Hemel: “The next generation of planners, architects and designers will have to get used thinking big, so making reference to big environmental challenges and mayor expected world population dynamic. Architects in particular will find themselves less and less powerful. We therefore have to focus on making our work more “information based” or we might get side-lined and more and more irrelevant”.

Find out more: http://www.iba-bv.com/