“I think artificial intelligence will make everything much faster. You’ll have decision support tools: we’re developing one ourselves at the moment, we’re working on the first 7D BIM project we don’t believe it’s been done anywhere in the world before, which is a BIM model that will have whole life cost and whole carbon data embedded in the model, so as you develop it from concept through design, through construction, through to occupation and use, it can automatically tell your clients how the whole life cost will change for thirty years.“

James Pickard: I guess my journey in architecture started when I was five years old. My father, who was a lawyer and was successful enough to build a very modern house, commissioned a good architect who was a professor at the local school of architecture at the time and he designed and built a very, very modern house that got published in magazines. And it inspired me as a five year old: I thought “Wow! This is amazing”. I saw the architect’s model, I used to go and see the house being built with my mom. She was an artist and my grandfather was a builder, he had a construction company, so I got this master builder aspect combined with some artistic influences.

Andreea Robu-Movilă:It’s a perfect match!

J.P.: Yes! At the age of five I ended up doing flat plans of apartments and drawing furniture and door swings. I was always interested in arts anyway but at five years old my imagination was caught by being very, very lucky and seeing the process of design and construction of a very modern house, which I then lived in, until I went to university. That house had a very positive impact on the way our family lived: it was great for parties and we had lots of big family parties and get-togethers, so I’ve got a lot of very fond memories of my childhood growing up in that house. That, I guess, is the principal reason why I felt architecture was something I wanted to do.

A.R.M.: Did you have any mentors during your studies or during your training as an architect?

J.P.: Well, there’s a bit more of the story before that. When I was in school I found out that I am quite heavily dyslexic. I think it’s quite common for architects that the visual side of the brain becomes much more dominant when you’re dyslexic. School was incredibly hard for me but once I finally got to university to study architecture, that’s when I really realized this is what I’m good at, this is what I was meant to do and that the spatial side of my brain was able to really go into overdrive. The principal architectural mentors for me are architects like Alvar Aalto and Sigurd Lewerentz, a Swedish architect. Very Scandinavian influences, I know, and Asplund. Shortly after I qualified, I went to work in Stockholm for a couple of years and really soaked up Scandinavian design. I think I found my roots in terms of my architectural thinking in the works of those architects.

A.R.M.: Which values do you consider as being relevant in an architectural career?

J.P.: I forgot to mention Jørn Utzon was one of my other big heroes. So, the principal qualities for me are always having a strong social agenda in what you’re doing. Buildings should not be ends in themselves, they shouldn’t be objects, they shouldn’t be for the gratification of an architect. All too often you see these “grand projects” around our objects: they look amazing, but the social value is zero. As a designer, I’m always very conscious that all the projects we do have a strong social value. I’m also very interested in using resources – that’s money and materials – and energy in a very responsible way so every building we’ve built has always been a very environmental friendly building. We’ve maximized and pioneered this off-site manufacturing – taking the building site into a factory is a far more efficient way of building: much less waste, lots fewer snags and defects on site and much safer.

A.R.M.: So most of your projects are built in a factory?

J.P.: A lot of them had been built in a factory or components built in a factory and brought to site. You have much higher quality of construction, shorter time on site and far few people get injured or killed. For example, on a British building site you’re eight times more likely to be killed or seriously injured than you are on a factory: and the UK isn’t one of the worst places in the world for deaths on building sites, but a lot of people are killed on construction sites – scaffolding is one of the most dangerous activities. We design a lot of our projects with zero scaffolding and that’s another strong social value we are adding. I’m passionate about how you make buildings fundamentally: the materials you make them from, avoiding waste and designing buildings that do what it says on the tin. They’re supposed to be providing homes that are successful for people to live in and have a happy life and not be well designed homes that function as homes, not beautiful objects that make the architect happy – actually those homes are rubbish inside – and if I were to criticize my own profession, I think architects all too often fall into the trap of believing that the best architecture looks glamorous, exciting but really are amazingly different and is often very, very extraordinary, but actually it is unsustainable bling and it is not really adding much social value.

A.R.M.: But you see, rewarding some of these glamorous projects is done by architects, not the public. This is a problem inside the profession.

J.P.: It is! There’s a very large ego and vanity within our profession that drives one aspect of it. You know, you’ve got to believe in yourself and what you do because no one else will and it is hard – I set up my business 23 years ago – but I think professional arrogance and vanity is worse. Some architecture firms go way off and you see these enormous projects, assignments needlessly expensive, exotic, adventurous and different, for the sake of being different.

A.R.M.: Do clients come to you for the reason that you approach architecture in a very sensitive way?

J.P.: I’d like to think we are very pragmatic and able to work with very tight construction budgets. We think we’ve produced really good buildings with very, very tight construction budgets. Obviously, there are some very famous, very successful architects who have consistently produced some very, very good work but I think there are still a large number of these grand projects that are over-designed, far more expensive than they need to be and really without no sustainability credentials at all. You know, it’s fashion… But is it architecture? To me, architecture has to be fit for purpose, it has to be sustainable and it has to use resources in a responsible way within the current environment. We have the problems of climate change and the economic crash and the meltdown of the Western economies, so we have to make the best use of the scarce resources we have. I guess that’s where my roots are, rather than in the glamorous, fashionable world that some very well known architects are able to operate in. But I am really pleased to be able to work in a well grounded area of design where we see, we get back to our buildings, we interview the clients, we measure the energy they use… We have buildings where the local authorities told us the rate of staff absenteeism through ill health has fallen by 30% when they’ve moved into our buildings. That’s had a massive effect on the well-being and of course, the productivity and effectiveness of the local authority. Being able to measure how buildings actually perform is something that my profession rarely does: it’s all about looking fantastic. I think we all know there are many, many design awards where juries don’t actually go or even visit the buildings and this says it all, to be honest. You can’t have an architectural award unless there’s a jury that bothers to go and see every building they have shortlisted. I don’t want to sound too cynical and I believe architecture fundamentally is an incredibly positive profession to be in: it is very undervalued in many countries including the UK. There are lots of very talented architects in the UK and elsewhere.

A.R.M.: Do they dedicate their lives for the well-being of others?

J.P.: Absolutely! I think, like all professions, there’s still a lot of area for improvement. If you actually look at the origins of the word “architect”, which I believe goes back to ancient Greek: arkhi and tekton. Tekton – to build, arkhi – to lead the process, to conceive the idea and lead the process. Being leaders is one thing but actually the tekton origins of the word “architect” is to build and the way you build, not just designing some amazingly extravagant building that wins a competition because it’s exaggerated, but understanding how you build that building with as few people getting injured or killed as possible, with using highly sustainable materials and thinking about the whole life of that building for the next sixty years.

A.R.M.: How you look at the evolution of your profession over time?

J.P.: Well, certainly in my own country, architects are becoming more and more marginalized and certainly in my career – I’ve been a qualified architect for over thirty years now – from when I started to where I am now, the way construction industry has changed, architects are trusted less – there are a few notable exceptions – but most architects in the UK struggle for the society to value what architects do. That is actually a real shame and I think you can go to other countries where society values architecture much more highly. I think architects are their own worst enemies in a way and if you don’t serve society well, if you are not adding a lot of value and you seem to be getting in the way of the process to get buildings built effectively, if architects don’t understand costs, don’t understand how you build, don’t understand the program and are not interested in some of the other “boring” commercial issues, we will continue to be marginalized and we will end up being like interior designers on the outside of buildings. We will have much less involvement in the technology of making the building.

A.R.M.: This decrease in relevance is due to the factors determined by architects or to the market?

J.P.: I think the education of architects in my country is not where it needs to be.

A.R.M.: It’s not adequate for the market’s needs?

J.P.: I don’t think it’s modernized, I don’t think it has recognized all the changes in the industry. For example, a number of students I interviewed don’t use BIM and BIM is fundamental now to work in the construction industry. There is a very high proportion of architecture students coming out of university without really understanding or having any experience with BIM, which is a shame. To me, that’s an example of a lack of understanding: architecture schools are missing some key things, including how you build and sustainability and these subjects should be taken seriously.

A.R.M.: What qualities do you believe that should define the profile of a young architect?

J.P.: Obviously, the ability to design is the number one, the most fundamental activity that an architect needs to be good at. I am also interested in people that have a wider view of life, a wider view of the industry they’re in, a knowledge of other aspects: they might have an understanding and an interest in materials, ecology, landscape, manufacturing or climate change. There are other areas… technology, its impact and all sorts of different aspects of technology on design and the way we make and deliver buildings.

A.R.M.: So he or she should outline a complex profile, rather than a specialized one?

J.P.: You know, technology is so much more important now than it was thirty years ago in how we design buildings, but also in the whole process of collaborating with other consultants, producing the information that manufactures can use to make the building. But also we should be pushing more and more to a manufacturing process away from manually building in muddy fields, in the rain and in semi-darkness, it is not the way of the future for building buildings efficiently. Architects should be at the forefront of creating far more value for the resources used and money in particular: a bigger bang for the buck, if you’d like, whereas I think that the focus of architecture training is still very much about object buildings and an experiential aspect of architecture, which is all well and good but it’s a narrow focus. Architects need to be far more multivalent, far more interested in other aspects: manufacturing, environment, ecology.

A.R.M.: To sum up, I would ask you what is your main source of happiness in architecture?

J.P.: I guess my main source of happiness in architecture is “no pain, no gain”, they say setting up Cartwritght Pickard 23 years ago. The first ten years were tough, but I’m very proud of what we’ve achieved, I’m very proud of seeing the buildings we’ve produced and it is a team effort in our office.

A.R.M.: How big is your office?

J.P.: About 45-50 people. We’ve got three offices: Manchester, Leeds and London. But I also get a huge amount of pride out of getting young students out of architecture school, helping them get their professional qualifications, giving them relevant experience, seeing them turn into great project architects and “flying”. Even eagles learn to fly or jump out of the nest, they’re falling, they’re going to hit the rocks but they flatten their wings and eventually they go off. And I get a really big kick out of that. In my practice in the last 20-30 years, we’ve estimated we have trained and produced at least 60 architects. We have effectively kicked them out of the nest and they’d been falling down about to hit the rocks, flattened their wings and off they’ve gone. It is really satisfying to see that! I think I’ve learnt to really engage with the millennials in my practice who are so tech-savvy and I have so much respect for the generation below me and their understanding of technology and how we can master and use that to the benefit of the business.

A.R.M.: What do you think that is the great potential of technology in architecture today, taking into account the fear that artificial intelligence will have a negative impact on the field?

J.P.: Absolutely on the contrary, I think artificial intelligence will make everything much faster. You’ll have decision support tools: we’re developing one ourselves at the moment, we’re working on the first 7D BIM project we don’t believe it’s been done anywhere in the world before, which is a BIM model that will have whole life cost and whole carbon data embedded in the model, so as you develop it from concept through design, through construction, through to occupation and use, it can automatically tell your clients how the whole life cost will change for thirty years. This is really intelligent, smart digital technology planted into architectural design. This is what will make architecture really valuable and not just kicked around by contractors anymore. So I think embracing technology is a massively powerful tool that helps us use our inherent creativity, which is the amazing thing about architects. They have so much creativity and value to add and problem solving that we need to find better ways of using that effectively in the industry we work within in order to be valued better. As we all know, architects are generally paid fairly low salaries – it certainly is the case in the UK – compared to most other professionals. That’s simply a product of the value that the society and the construction industry currently put on an architect’s role.

A.R.M.: That’s the sad truth with reference to the relevance of architecture.

J.P.: And architects have deskilled themselves over decades.

A.R.M.: Why do you think this happened?

J.P.: I think it’s because architectural training has become focused in a very, very narrow area of design and architectural thinking, at the exclusion of a plethora of other areas including technology, construction methods, manufacturing, sustainability and we’ve been abnegating these responsibilities, we’ve been deskilling. So now, in large projects, the architect will have a cladding consultant, an acoustic consultant, a fire consultant, an access consultant: we’ve got a consultant for all these things that architects now longer want to do.

A.R.M.: So we seem to complain that we’re letting parts of our profession be taken by other specialists and we find ourselves dominating one single aspect of the profession. Does this probably reflect the problem with the relevance of architecture today?

J.P.: Yes! Some of the really big, famous, global architects are lucky because they are working at a certain level where focusing on that one aspect of design is working for them. But for the vast majority of architects, I believe the world over. We’ve got such a fantastic education, we’ve got so much to offer but for all sorts of different reasons we’re not being valued by society the way we should be and I think we’re missing a lot. Certainly, as I said, digital technology could be one of several key areas that if architects grab it, they become the leaders in the process.

A.R.M.: They have the chance to win back the lost territories.

J.P.: Yes, they become the leaders in the process: archi-tect. Leading the construction process: digital technology is one of the keys to that and we need to be the masters of it. Everyone has to come to an architect if they want to solve and coordinate all these issues and that’s what we need to be.

A.R.M.: We need to have all the needed information in one place.

J.P.: Yes! Program costs, performance, life costs: they can all be built into our model. The architect can become so powerful and therefore adding a huge amount of value, if we’re prepared to go and grab it!

A.R.M.: Thank you very much for your time!

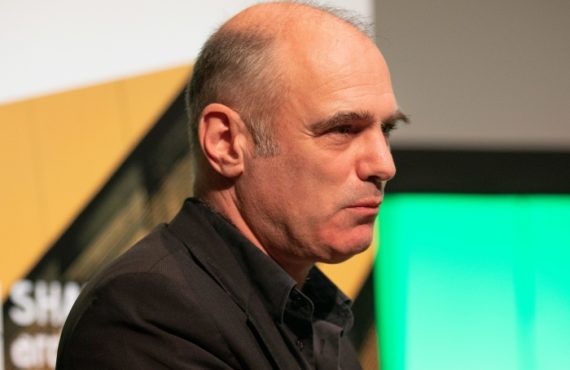

James PICKARD

James Pickard co-founded the practice with Peter Cartwright in 1997 and runs our London office.

He has market-leading skills in housing design, with a particular strength in developing buildable, viable schemes for challenging and complex urban sites and has helped the practice to develop a reputation for innovation and the practical use of offsite construction methods, with a particular focus on lean, low carbon solutions, air quality and wellbeing.

James also has a particular expertise in workplace design and has recently overseen the London Borough of Lambeth’s new civic offices and refurbishment and transformation of Brixton Town Hall. He is currently involved in the design and delivery of a major new civic office and residential scheme for Crawley Borough Council.

James has a passion for research and has carried out government funded research work into the design of low energy buildings and office occupier productivity as well as a running a current KTP into the potential for 7D BIM.

He was invited by the Department for Communities and Local Government to sit as a steering board member and contributor to the Urban Land Institute’s ‘Build to Rent’ best practice guide for the private rental sector and sat on the main board of Constructing Excellence between 2005-2006. James has been an assessor for several industry award schemes including the Civic Trust and is an Honorary Professor at the Glasgow School of Art for his contribution to the Mackintosh School of Architecture.

Find out more: https://www.cartwrightpickard.com/